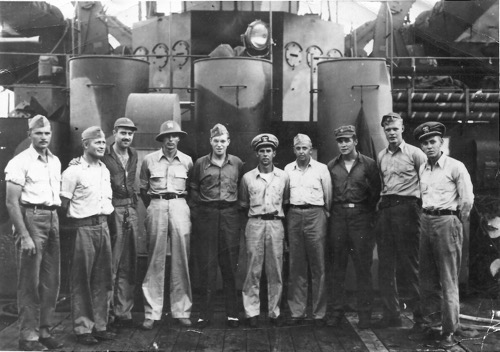

Hi, this is Allison Sheridan and you’re listening to Chit Chat Across the Pond episode #463 for November 10th, 2016. This week’s recording is very different from anything I’ve done before. This story took place on September 16, 1945. On that date a horrific typhoon hit the island of Okinawa, Japan during World War II. My father, Ensign John Paul Moorhead, was serving as Chief Engineer aboard the LST 965 and was in that typhoon. He wrote a letter to his parents and my mother describing the harrowing experience of living through that typhoon.

I thought about reading my father’s letter aloud to you, but it didn’t sound right in my voice. I asked my dear friend and noted voiceover artist Ron David to read the letter to you instead. You may recognize Ron’s voice from Raise The Titanic on National Geographic and Wings on the Discovery Channel.

Before we hear the letter, I’d like to give you a little background. The ship on which my father served was an LST, which stands for Landing Ship, Tank. LSTs were amphibious ships designed to bring cargo and troops to unimproved shorelines.

I remember my father explaining to me that the LSTs were never expected to last long enough to come back home, because they were designed and assembled in such a hurry that they weren’t likely to survive for very long. I read online that the contracts were let to build the ships before a single test ship had ever been completed. This is not the kind of ship you’d choose to be in, in a typhoon.

The typhoon you’re about to hear my father describe reached winds of 150 miles per hour, beached 122 ships and small boats, sank five others and killed or injured hundreds of American service personnel. Since this week is Veteran’s Day in the United States and Remembrance Day in Canada, I thought it would be an appropriate day to bring you this very special Chit Chat Across the Pond.

I’ve included the full text of my father’s letter in the blog post along with a few snapshots of the ships aground after the typhoon. If you want to know more, I’ve included a zip file of four news articles my father kept that you can download.

And with that, I’ll let Ron David read my father’s letter to you.

18 September 1945

If I don’t write now I’ll miss the feeling of this experience. It seems a million years ago that I wrote home. I will start with our trip down from near Kobe to Nagasaki, Kyushu. We were about halfway there when storm signs started showing up and we reversed course to run before a typhoon.

We saw swells as high as the ship but managed to reach the harbor we had left and drop anchor before the full fury of the storm hit.

Even in this land-locked bay the waves became large and the winds over the mountains were terrific.

I had the 4 PM to 8 PM watch and toward the end of it we commenced dragging anchor. By that time nearly all the smaller craft were underway as their anchor wouldn’t hold. We managed to return to our anchorage but still the anchor wouldn’t hold. I was just too thrilled by the violence of the wind, so I stayed up.

By midnight the wind had increased to such force that it was almost impossible to stand erect on the main deck.

The rain cut like pellets of ice, tore at our eyelids, and threatened to tear off our clothing.

The wind was so strong that as I was struggling to the front of the con, it broke my grip – picked me up and threw me back 3 feet against the rail. The bow would go down and solid sheets of green water would be carried over the deck to pound up against the deck housing.

The wind made the whole deck housing shudder and the pressure beat on your eardrums until you thought they would burst. Went on and on until you thought you couldn’t stand it any longer.

During the worst part of the storm Jake and I fought our way to the bow end and I argued him into going below for a life jacket and just as he went I saw a ship bearing down on us from the port side.

It was going to hit by the hatch leading below up forward so I went to the port side and sent below to have that side of the ship cleared of personnel.

It was going to hit by the hatch leading below up forward so I went to the port side and sent below to have that side of the ship cleared of personnel.

The captain sounded a collision then. The ship was 100 feet off and coming on 20 feet every time a wave hit it. It was eventually (a few long seconds) only 20 feet away and looked as though it would hit right between my feet.

It was a large ship with a sharp bow (I thought my imagination made it look larger until I saw it on the reef today).

The bow would come clear of the water and I could see the chains of both anchors she was dragging streaming from her bow.

Kept thinking the next wave would send it cutting through us and couldn’t make up my mind which way to go as I was sure the stern would sink and the bow turn over because both anchors were on the port side.

I could see the people in their wheelhouse dashing about and could feel eternity staring me in the face.

She started backing down and the captain got us swinging to starboard. Gradually she moved on our side bow towards us, getting closer all the time.

Back by the small boat it only cleared by two or 3 inches and by the stern about 2 feet.

Jake got back up in time to see me there and he claims I was grinning at it. Don’t know what my expression was but I sure was mentally pushing it back.

It looks to be a ship considerably larger than ours. I will see it in nightmares for years to come.

At about 2 AM we were only 600 yards off the breakwater and dragging anchor fast.

I went below to wake the men and while I was there, there was a terrific jolt and a rending of metal.

We were on the reef.

I did the best I could to calm the men and sent those who were needed below to find the extent of the damage, and do what they could to remedy it.

I reported to the captain and then went below myself.

I reported to the captain and then went below myself.

We were rolling and tossing very badly. The stern of the ship was aground on a Jetty built of concrete piles and jagged rocks and we were about 50 feet off the built up break-water which was about 100 feet wide, a mile long, and not connected to land at either end.

The waves were breaking completely over it. Our after-compartments began to be punctured and take on water.

By 4 AM three of the four shaft alley compartments in the boiler room were flooded. Some of the boys were panicked as the future looked pretty dark, but the men I had counted on were all still “cool”.

The general opinion was that unless the storm abated very soon, the ship could break up.

I ran up from below-decks and threw some things I didn’t want lost together and assembled the records I would have to save.

It is funny how values change at a time like that. The main things I wanted to save were the pictures of you.

I still had faith in the ship and wasn’t about to trade it’s warmth for the doubtful safety of a spray drenched pit of land even though it was only 50 feet away.

Just about this time water started leaking through the shaft packing into the main engine room.

I had tried to start a letter while standing by down below but didn’t make the grade.

All at once the wind died down and the ship was left bleeding but unbroken on the rocks.

As the sun came up we started to make a complete survey of all our damage.

The captain was feeling very low and asked me if I would bring him cigarettes on visitors day as they put people who run ships aground in jail.

I looked around for some news to cheer him up but the further I looked, the worst things seemed. The port rudder was bent over about 10° and the bottom support was missing.

The starboard rudder had been carried away completely.

Both screws were badly beaten up,

Both screws were badly beaten up,

By this time I was about shot and things looked pretty black.

As bad as I want to come home I don’t want to do it with old 965 rotting on a reef.

I turned in for a little sleep after ordering some of the men to pump out the forward starboard shaft Alley to get the water pressure reduced in the main engine room.

I awoke with a start about an hour later with the idea to try turning a remaining rudder, using a hand apparatus, and then to try turning over the screws by hand.

One of my men and I went below and switched over to hand steering and we were able, with some strain, to turn the rudder enough both ways to show it was still partly usable.

Then we turned over the screws, tried turning them with the engines, and found they would work.

We knew, however, that if we got underway with them, the vibration would be bad.

The boys had a compartment they had been pumping out drained, and found the water was coming from the after-compartment, and could be stopped by getting the hatch dogged down tighter.

We found that the port shaft alley had also held, even though the bulkheads had bulged. So we weren’t nearly as bad off as we first expected.

We found that the port shaft alley had also held, even though the bulkheads had bulged. So we weren’t nearly as bad off as we first expected.

Last night as I started writing this, the moon was shining brightly on the placid waters of the bay.

The swells were splashing against the offshore side of the ship. It seemed hard to realize that only a day before there was such turbulence.

Today another LST tried to pull us off the rocks with no success.

I wanted to get rid of about 190 tons of fuel which would lighten our weight making our of floating off much better.

It’s breaking my heart but I’m also dumping a whole tank of fresh water.

We still have the topside evaporator to run so we do have some supply. That unit has been a godsend.

When the tide was out we tried to patch and shore up the holes in the starboard shaft alley but we couldn’t stop the water.

I want to be able to use the starboard screws as the vibration would loosen the packing around the shaft and let the water into the forward shaft alley compartment and from there into the main engine room.

They’re going to try pulling us out, bow first, tomorrow and I’m almost certain we will puncture the port shaft Alley in the process and lose our fresh water pumps.

If we do get off the rocks I’m still not sure what they will do with us.

I’m sort of doubtful that they will fix us up, even though we are in pretty good a shape as we are. The Navy is going to have to decommission most of these damaged vessels anyway.

Whatever happens I expect Wilson and I will be on board for some time, as we will have all sorts of paperwork to take care of and lots of material to dispose of.

I don’t know when I will get this letter off. We’ve aged 10 years so many times we should’ve died of old age long ago. Which reminds me I’m going to tell the captain I want five more points for the 10 years. I’ve aged.

If we are eventually taken off the ship I don’t know what (will be done) they will do with us.

If we are eventually taken off the ship I don’t know what (will be done) they will do with us.

The typhoon is now over but has left us feeling like hour glasses with all the sand drained out of them.

This morning I went up and counted noses and there were only 14 ships left counting ourselves and 53 or more major ships on the rocks.

When the final accounting is in I think it will be found that this was the worst storm recorded for this area.

Normal barometric pressure at sea level is 29.92 inches. Yesterday it dropped to a value I never heard of, reaching 27.96.

The wind was more than 100 miles an hour.

They tried to pull the bow off but only moved it ten feet. I’m afraid we may have just become part of the Japanese coast.

The waves and the sea are also building a sandbar between us and the bay.

We had a salvage survey made of the ship today by two captains, a commander and a lieutenant. They said they would make every effort to get us off the beach but that the odds were 10 to 1 that we would be scrapped anyway.

It would take an act of God to get us off the reef just as it did to get us on.

We learned today that there are 21 ships on the beach at Okinawa, one at Kyushu and four here. The incident made the papers. I don’t know if our ship was named, but I saw an official photographer take a picture of us.

I salvaged about $1000 worth of equipment from the boiler room today at low tide.

This is so far the tale of the 965. Part of me will die with her, you can’t work and undergo danger on a ship without becoming part of it.

I expected it to finish its stay at home – not rotting on foreign soil.

It has been quite an ordeal, I’m pretty beat, so I’m going to bid you all “Good night”.

Love to you all.

Jack

Allison,

Thanks for sharing your father’s description. Fascinating.

If you’re interested in related descriptions, look up the fictional depiction of a Navy ship going through 1944 Typhoon Cobra in Herman Wouk’s famous novel The Caine Mutiny. It’s really good and I like the Audible version.

(We have great cameras now, but you rarely see glamour apparent in the pictures of your mom. )

Best,

Paul

What an absolutely horrific experience to have survived. He must have felt so totally helpless, while trying to keep his men from panicking. Thank you so much for sharing his experiences, so many if which went untold.

Just finished listening to the recording of Ron reading your dad’s letter. I felt like I was there! The words of your dad and Ron’s voice painted a vivid picture of what the experience must have been like. If your dad wasn’t as calm during the storm and the aftermath as he projected in the letter, he did a great job of conveying it to his family. Thanks for sharing, Allison!

That’s an amazing story, and thank you for sharing! … And the narration was a perfect fit.